Kids online these days are self-diagnosing with psychiatric disorders that are far more severe than any diagnosis they would receive from a therapist or psychiatrist. But why is that? There are two key reasons I'd like to focus on, which are more or less interdependent:

That it is to say, I would like to reframe the question: Why are the kids self-assigning a different caste than they would receive from a member of the clergy? By framing the question this way, perhaps we can begin to explore the differences between institutional psychology and the folk practices of psychologist laypeople.

Schizophrenics are the mystic caste of the religion of contemporary folk psychology.

Or, to put it another way, the schizophrenia of our time is madness par excellence, and inherits more than any other of its siblings the signs associated with the madness of the Middle Ages, as outlined by Foucault, namely that of the mad person's direct experience with occult knowledge. Certain Internet communities exist at the convergence of "gnostic" or "occult" communities and "bad schizo" communities, consisting of schizophrenics who are opposed to the "clean schizophrenia" marketed by those of a "recovery from" and therefore, to a certain extent "transcendence of" schizophrenic tendencies. The "bad schizos" are not necessarily or inherently marked by particular religious leanings, but rather by a sort of so-called anti-recovery strain of thinking, wherein institutional psychology is partly or fully rejected, either because of its necessity to the carceral form, and an alternative, usually phenomenological, approach to understanding schizophrenia is adopted.

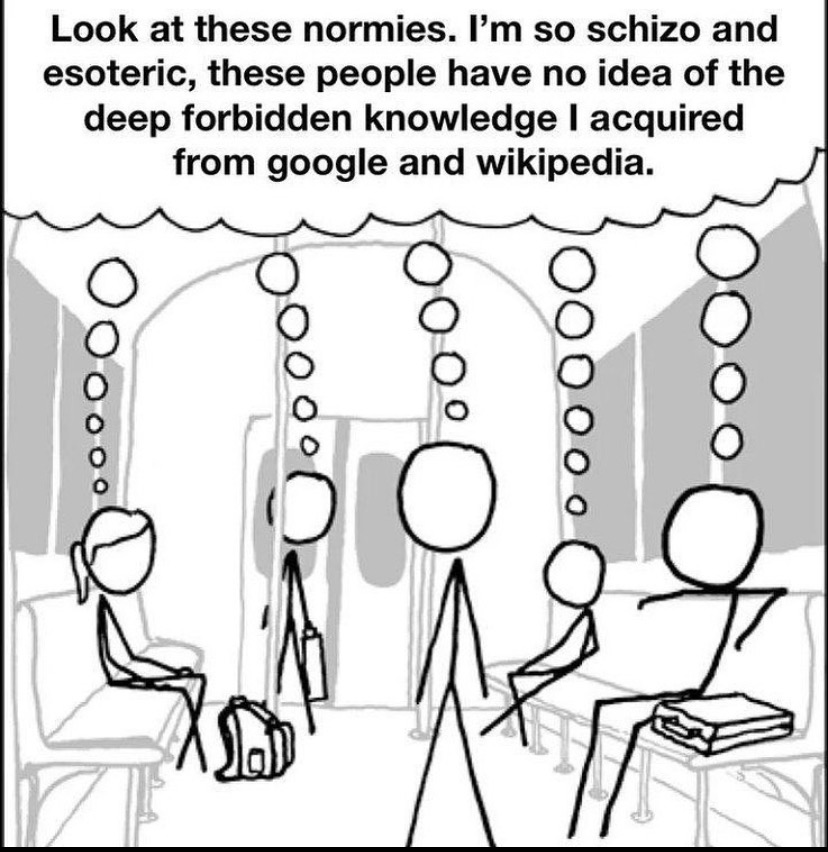

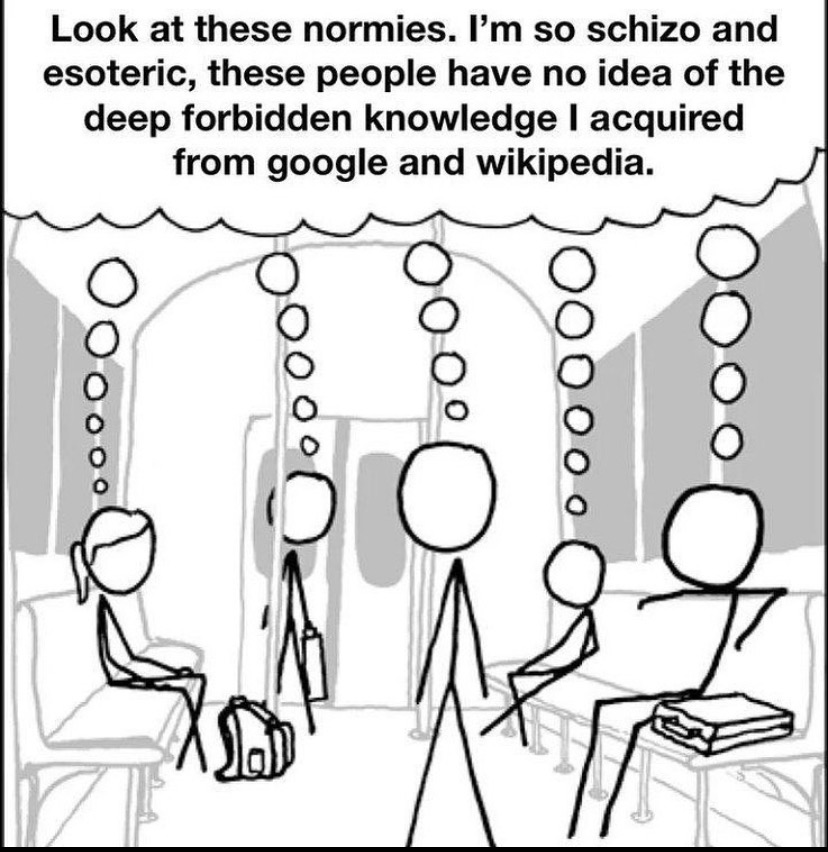

That said, it should be noted that this schizo-gnostic strain is populated predominantly by non-schizophrenics, though usually community members are or are eligible to be diagnosed with some other psychiatric disorder. Rather than the convergence of anti-psychiatry and occultism taking place on the level of communities, it's instead a kind of cultural syncretism, wherein these "bad schizo" ideas are appropriated on behalf of occult "folk psychology." Schizophrenic, as a term denoting a kind of in-group among psychiatric survivors, comes to "schizo," meaning "esoteric," or "post-reason/sense" more broadly. The term schizo is adopted precisely because it is a monastic term used by orthodox psychology, rather than simply "mad," precisely because it is outdated and no longer carries the stigmatic weight of the contemporary "schizo" or "psycho." It's rebellious to be mad, therefore it's rebellious to be a schizo, and 20th century thought, particularly in France, has laid quite a substantial foundation for contemporary fascination with madness, and its transition into "schizophrenia."

It's possible that this shift from madness/insanity/etc. to schizophrenia as the term denoting unreason par excellence is due to orthodox psychology's abandoning the category of neurosis while retaining psychosis (which also had a significant impact on other diagnoses such as BPD). Because orthodoxy abandoned neuroses as a category of unreason in favor of behaviorist apologia ("neurotic behavior is actually perfectly reasonable if understood in light of such and such event in the patient's history"), all unreason is relegated to the category of psychosis. But two things occur as a result of this. 1: People suffering distress from certain mental phenomena may not accept orthodoxy's reasonable explanations and instead view these phenomena as unreasonable, thus understanding them as psychotic. 2: Those who view unreason as fashionable (e.g. people of fringe political inclinations who view reason as a tool of authority/the State/etc.) may find it more stylish to accept the "schizo" or "psychotic" label over a diagnosis they'd be more likely to receive from a practicing therapist which has been more thoroughly incorporated into the monastic & carceral power structures, such as various anxiety or depressive disorders.

But why self-diagnosis at all? Common apologetic arguments for self-diagnosis have to do with inaccesibility: professional diagnosis is, after all, expensive. What is not often acknowledged, however, is that self-diagnosis asserts autonomy. I would argue, in fact, that self-diagnosis is essential to today's American religious ecosystem, where psychology dominates. Because diagnosis is, despite being marked by medical language, really a kind of caste-assignment carrying distinct identitarian and metaphysical weights, self-diagnosis is a kind of self-actualization akin to that offered by heterodox folk practices such as use of the malocchio to ward off bad luck vs. obtaining blessings from a priest/accepting the dominion of God over human affairs. Diagnoses hold a kind of religious power over people, and despite voices within and without the psychologist community attempting to steer laypeople away from treating diagnostic categories as essences/identities, this usage is nonetheless widespread. Beyond that, to ignore the caste-like nature of diagnostic categories is to ignore the intense social stratification present within the religious community, especially within carceral spaces: think on how people suffering from depression are treated in psych wards (and in general) vs. people with personality and psychotic disorders.